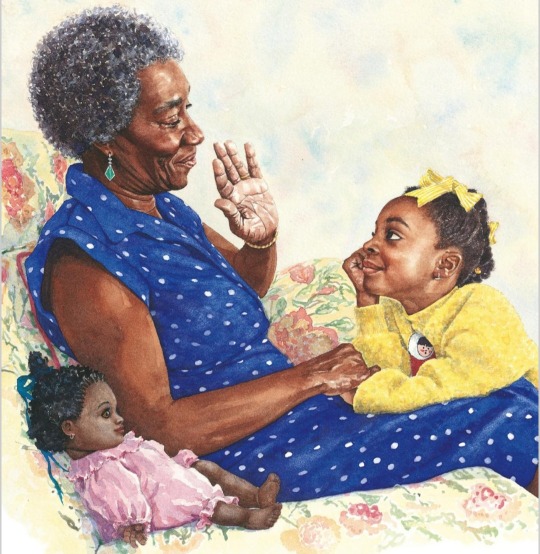

#mary Hoffman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

IYKYK

#imanisaysboard#throwback#black girl nostalgia#black woman appreciation#black books#black girls read#mary Hoffman#amazing grace#books and reading#childhood reading#black girl moodboard

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

So … I‘ve re-read Stravaganza, City of Mask by Mary Hoffman quite recently. Now I‘m reading City of Stars.

And I saw the little ad on one of the last pages for the Stravaganza webpage, where you could find out your Talian name and stuff. And The memories came rushing back to me how I spent hours on this website, it was so much fun.

And now it‘s just gone?? I wish I could browse through it again, re-discover it all over again. I really liked it.

I wonder if anyone else still remembers it??

#stravaganza#mary hoffman#stravaganza city of masks#city of masks#city of stars#stravaganza city of stars#personal

16 notes

·

View notes

Quote

There are some choices you can only make once. You can't go back to where you made a choice and then take the other one.

Mary Hoffman, City of Flowers

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under the Walls

The following short story written by Mary Hoffman is from the official Stravaganza-website, which doesn't exist anymore. It is accessible through the Wayback Machine, but I am uploading the short stories here to a) act as a secondary archive and b) to make them accessible to fans. If this story is ever re-published somewhere or I am asked to delete it, I will do so. This post will be unrebloggable, but feel free to link to it if you wish to add comments/discuss the story. I do not own the story, and it is directly copy-pasted from the old website. (Sorry for the weird question marks in place of quotes, that's how the text looked like on the website)

---

Carlo di Chimici* was not a happy man. His older brother, Fabrizio,* had made himself Duke of Giglia, married and produced four sons in quick succession. It was quite clear that he saw himself as the head of the family in waiting, as soon as their father was dead. Their two surviving sisters hardly counted; women were not important in the powerful di Chimici family. Their role was to look beautiful and produce children, preferably sons.

Carlo had a beautiful wife himself — Eleanora — who had presented him with a son as their first child, and then a daughter. But there were also some lost babies and no other son had graced their marriage. It was looking now as if there would be no more.

So little Jacopo — now aged four — was very precious. But what was he to inherit? Some son of Fabrizio would have Giglia and it was clear that the family was expected to take over more Talian cities, to create more mini-dynasties for generations of di Chimici Dukes and Princes to rule.

?It was easy for Fabrizio,? Carlo grumbled to his wife one hot night in the summer of 1459. ?We live here in Giglia. Strictly speaking our father should have been Duke before my brother was but he just sat back and let my brother have all the power and the title too.?

?Your father is old, dearest,? said Eleanora. ?And tired. He was happy to hand the business over to you and your brother.?

?Huh, there is not much for me to do,? said Carlo. ?Father and Fabrizio have it all wrapped up between them.?

It was true that he did work in the family perfume business but he never felt truly at home there. His father and brother were branching out and becoming bankers to the great houses of Europa, the family wealth growing day by day. But Carlo saw himself more as a man of action and he was restless.

Then one day he was sent with an order of perfume to a city he had never visited before. It was north and west of Giglia and was called Fortezza. It was the best place in Talia to buy a new sword and he came with a commission from his brother to buy him a new weapon, once the perfume business had been completed.

I wonder, thought Carlo. Could I make this city mine?

But he had no idea how to do it, except that it would take a lot of money; and, although he had a fine palazzo in Giglia and plenty of money to buy himself a new sword, he didn?t have the sort of wealth that would enable a young man to buy himself a city.

He was in a swordsmith?s workshop when a sweating messenger tracked him down.

?Back to Giglia, Signor,? the man gasped out. ?Your father . . .?

Carlo didn?t wait for the rest of the message. It could mean only one thing. He ran back to his lodgings, gathered up his things and was back in the saddle before the messenger had properly recovered his breath.

The miles fell away under his horse?s hooves but by the time they clattered into the courtyard of the Giglian palazzo, it was already too late. Alfonso di Chimici was dead.

Fabrizio, the newly minted Duke of Giglia, was pacing the salone.

?Ah, brother! You are back.?

The men embraced awkwardly, feeling it was expected of them, while their sad-eyed mother looked on.

Within days in that hot summer, old Alfonso had been buried and mourned.

And then Carlo found himself suddenly rich. He had not had any idea until then how much wealth his father had amassed. Even with dowries for his sisters, Francesca and Lucia, and the substance of the perfume and banking businesses being left in Fabrizio?s hands, there remained an impressive sum for the younger son.

He went straight to his brother?s palazzo and had himself admitted to Fabrizio?s study.

?I need your advice,? he said abruptly. ?I want to leave Giglia and try my luck in a new city.?

?Where will you go?? asked Fabrizio.

Carlo noticed he was not going to try to persuade him to stay.

?I want to return to Fortezza,? he said. ?Now that I have inherited some money, there are things I could do there.?

He didn?t specify what but Carlo had decided: if Fabrizio was going to be a duke with a banking business, he would become a military man with an army, a soldier-prince perhaps.

Carlo set off for Fortezza soon afterwards, leaving Eleanora and the children in the care of his mother.

In a very few months, the Signoria of Fortezza became sympathetic to this vigorous man and his schemes to protect the city, particularly since he was offering to pay for them all.

Carlo di Chimici drew up plans for a massive castle, to be known as the Rocca di Chimici, and, while the foundations were being laid, he set about recruiting soldiers for a permanent standing army.

It took two years for the mighty Rocca to be built and it was a proud day when Carlo moved Eleanora and their son and daughter into it. Little Jacopo was six now and was given a wooden sword. His sister Beatrice was only four and easily menaced by her brother.

Jacopo ran up and down the battlements of the curtain wall, waving his sword and uttering bloodcurdling battle cries.

Privately, Eleanora thought the castle was far from elegant, but she said nothing to dampen her husband?s pride in it and it certainly did feel very safe and well defended. Although she didn?t know exactly what it needed defending against.

As for Carlo, he felt he had found his mission in life, defending his family and what he increasingly thought of as ?his? city.

It wasn?t long before he was elected the Signore of the Signoria and effectively Fortezza?s leader.

They had never had a noble family to lead them before and the di Chimici were building up a power centre in Giglia such as Talia had never known before. And lots of that di Chimici fortune was coming Fortezza?s way, what with the building of the castle, the creation of an army and lots of work for the city?s famous weapon-makers.

The members of the Stonemasons? Guild came to the Signoria with a proposal: now that the di Chimici castle was finished and was clearly such a strong fortress, would the governing body approve the building of walls all around the city itself?

The Signore, Carlo di Chimici, was all in favour and willing to pay half the cost himself so the proposal was soon passed and before long, an artist was approached to design the city?s fortifications.

Mariano Matrielli was a sculptor and painter who had lately come to be known by the newly defined skill of engineer. He was a testy and difficult individual but superb at what he did.

Carlo summoned Matrielli to the Rocca.

?Well, what do you have in mind?? asked the artist, not at all overawed by his surroundings in the great red salone of the Rocca.

?Walls to surround the city,? said Carlo, happy to meet another man who didn?t beat about the bush.

?All the way round? Continuous walls?? said Matrielli, rubbing his hands. He was beginning to get interested in this commission.

?Well, yes. But we?ll need some gates, and a moat, and I suppose some guardhouses — maybe some prison cells too.?

?You are expecting trouble? Some invasion or siege??

That was the trouble. There was no threat that Carlo knew of to Fortezza. He just liked the idea of an impregnable city — one that he could rule.

?It is always good to be prepared,? he said.<

BR>?I agree,? said Matrielli. It made no difference to him, as long as he was being paid and had a free hand in the design.

He was back a week later with drawings that took Carlo?s breath away.

Massive walls with twelve heavy bulwarks set evenly into them and so wide across the top that a platoon of soldiers could march twelve abreast!

With defences like these Fortezza would surely live up to its name and never be conquered. And there were tunnels inside the walls leading to banks of prison cells. And guardhouses in each bulwark and in the space above the main gate, which was not near the castle.

?Magnificent!? said Carlo di Chimici. ?I shall take them to the Signoria for approval but can?t imagine they will be anything except delighted.?

?Of course, if my plans are approved, I shall need a large sum of money to order materials and start hiring men.?

?Of course,? said Carlo. ?There will be no problem about that.?

He had recently heard that the King of Anglia had repaid a massive loan from the di Chimici bank in Giglia, together with considerable interest on the original sum.

The massive bastions were to be built first but before work could begin on their foundations, the old walls, now seeming very inadequate, had to be pulled down and the land outside the city cleared and levelled. Vast teams of labourers were employed in the city and the whole of Fortezza was abuzz about the walls and Matrielli?s grand designs.

At last it was nearly time for the foundation stone to be laid.

The week before, a visitor came to see Carlo one night He was a strange figure in a cowled robe and would not give his name. The only reason he was admitted was that he said he had an urgent message for the Signore about the coming ceremony.

?Who are you?? asked Carlo.

?My name is not important,? said the man.

?Reveal your face then.?

?My face is not important either. Do you want to hear my message or not??

?Say what you have to and get out,? said Carlo. ?You have already tried my patience.?

?These walls of yours,? said the man. ?Do you want them to keep out enemies??

?What a ridiculous question! Of course.?

?Then there is one more thing you need to do.?

Carlo felt uneasy; there was something sinister about this man and yet he had a compelling presence that was hard to ignore.

?This is a Tuschian city, built on the remains of one built by our ancestors, the Rassenans,? the figure continued.

?I know its history,? snapped Carlo.

?History comes with responsibility,? said the stranger. ?If you do not complete the rituals, the project will not thrive. However strong they seem, the walls will not keep out the enemy.?

Carlo felt his throat dry; he was not going to like these rituals, he was sure.

?What are you saying we should do?? he asked, more calmly than he felt.

?Blood,? said the man. ?The foundations need blood. You must find a sacrifice.?

For all that he was a man of action, Carlo did not like the unnecessary shedding of blood.

?An animal, you mean?? he said. ?A cockerel or a goat??

?Something bigger,? said the visitor. ?A man. Remember — without it the walls will fail.?

Then he turned abruptly and left the salone. It was almost as if he had disappeared.

?Stop him!? cried Carlo to his guards. But it was too late. Of the hooded man there was no sign.

Carlo spent a restless night. Of course what the man had suggested was out of the question. The official foundation ceremony had already been arranged and would not include even an animal sacrifice, let alone a human one. The very idea was preposterous.

And yet Carlo, like many Talians, was deeply superstitious and also eager to impress the citizens and Signoria with these walls. He was hoping they would agree to make him the city?s prince.

He was seriously thinking of postponing the ceremony.

And then a solution seemed to open up. A murder suddenly seemed to give Carlo a way out.

A man had killed his wife in a jealous rage; this was unusual for Fortezza, whose citizens were fairly peaceful. And, as it turned out, the woman had been blameless. Her husband had been condemned to death and was deeply penitent of the crime.

Was there a chance that the execution could be carried out at the site of the first tower and the body buried under the foundations? The man was going to die anyway; why not use him to appease the gods of the Rassenans? Carlo thought this could be the answer but still he didn?t know how to suggest it to the authorities.

His wife was beginning to worry about him. Carlo slept badly, was hardly eating, had taken to gnawing at the side of his thumbnail and was always distracted. He took hardly any notice of the children. Eleanora just couldn?t think what could be the matter. His building plans were going well, there was the beginning of a fine army and the family had settled well into their new home in the Rocca — even though for her part she would have preferred an elegant house in Giglia.

And then the Manoush entered the city.

In their colourful and glittering clothes, with long hair streaming and music playing, the group of wanderers passed easily across the ditch that had been dug around Fortezza in preparation for a moat. Citizens hesitated on the rickety plank bridges that had been thrown over the gap but this exotic group just flowed across, not missing a step of their dance.

Their leader was a tall woman, her long dark hair streaked with silver and threaded with ribbons. She was leading her people into the cathedral square when Carlo di Chimici, not looking where he was going, bumped into her.

?I?m sorry, Signora,? he said. ?I had my mind on something else. Please forgive me.?

?I can see that,? said the Manoush, scrutinising his face with her dark, intelligent eyes. ?You are troubled about something.?

She signalled to her people, who dispersed about the square.

?Would you like to tell me what it is??

And Carlo had the strangest feeling that he would like to tell this person, that she might even be able to help him.

They went into a tavern and he ordered wine for them both. Within minutes he had told her who he was, his plans for the city, and about the mysterious stranger who had told him of the bloodthirsty ceremony he should carry out.

?I have heard of him before,? said the woman, who had introduced herself as Daria Vivoide. ?And whenever I have heard of him, the word has not been good.?

?But is he right? Will all my plans come to nothing without this gruesome ritual? I have been going mad thinking of it. How can I tell the Signoria that we must mix human blood with the mortar or Fortezza?s enemies will be able to breach the walls??

?It is good to respect the old gods,? said the woman slowly. ?My people do not build cities — we are nomads. But I have heard of a ritual that might replace this cruel custom and still appease the local deities.?

Carlo felt hope for the first time.

?But it would not be without danger for the person who carried it out. It would be best done by one who does not expect to live long.?

Carlo told her about the murderer.

The day for laying the foundation stone dawned pearly-clear and cloudless. Long before the official party assembled at the site of the first bastion, Carlo di Chimici met a small group of masons, the engineer Matrielli and a few brightly-clothed people, including Daria Vivoide.

Soon afterwards a party of guards came from the jail, leading the wife-murderer in chains.

The wretched man shuffled along, his head down, as if expecting the worst.

Matrielli stepped forward with two workmen and moved the prisoner to a deep trench. The morning sun shone on him, throwing his shadow across the hole. The two workmen, directed by Matrielli and the Manoush, took the measure of it with a length of rope and then Carlo stepped forward.

?Throw the rope into the trench,? he ordered. ?And release the prisoner.?

The man rubbed his wrists and looked into the eyes of his rescuer. Carlo had explained the risks to him.

?I am free to go?? he asked.

?Absolutely free,? said Carlo. ?As long as you do not return to Fortezza.?

He put a cloak around the man?s shoulders, gave him a small bag of silver, and sent him on his way.

The little party watched as the murderer walked away, staggering at first and then straightening up, until he was a just a small figure in the distance — like a child?s sketch of a man.

?Do you really think it will work?? Carlo whispered to the Manoush.

?It is the civilised way,? said Daria. ?Once he would have been thrust into the foundations and buried alive. But the old cruel rites are being replaced over Europa. The burying of a man?s shadow will satisfy the gods but it is still likely he will be dead within forty days.?

?He told me he wouldn?t care,? said Carlo. ?He killed his wife. His children hate him. And it will be forty more days of life than he would have had. He was due to be executed today,?

Carlo heaved a big sigh.

?Thank you for your help,? he told the Manoush.

?Now, can we get on with the real ceremony?? asked Matrielli.

?As soon as I?ve had some breakfast,? said Carlo. He suddenly felt ravenously hungry. ?Come and have breakfast with me,? he said with an expansive gesture, including the engineer and the Manoush. ?We can?t start such an important enterprise on an empty stomach.?

Carlo cast one look back in the direction of the condemned man. Was it his imagination or were there now two figures on the horizon? It seemed to him that the first man had been joined by another, wearing a hooded robe, but it was too far away to see clearly.

He turned towards the Rocca, his heart lighter than it had been for many days.

* The Fabrizio and Carlo di Chimici of this story are not the ones we know from City of Stars onwards. They are the sons of the first founder of the di Chimici dynasty, as you can see from the di Chimici family tree.

#stravaganza#mary hoffman#I almost missed this last one because I had to go to the latest version of the website available to get it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaetano: [to Fabrizio] I'd like to not get involved in these matters, or any matters of any nature.

#source: parks and recreation#stravaganza series#stravaganza#mary hoffman#incorrect quotes#gaetano#gaetano di chimici#fabrizio#fabrizio di chimici

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you loved X, try Y...

If you loved Stravaganza by Mary Hoffman, try Kushiel's Dart (first in a series) by Jacqueline Carey, for splendid historical fantasy with romance and intrigue

#book recommendations#bookblr#reading#books#stravaganza#mary hoffman#kushiel's dart#terre d'ange#my posts

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Normalize giving Hoffman the fattest rack and the thiccest thighs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

As promised, the Amazing Grace study guide.

To request a study guide on a banned book, do the asks thingy and I will get to work.

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

#Marie Hoffman#No Farms - No Food#No Farmers - No Food - No Future#Food Security#Advocate for Agriculture#Support Local Farmers#Like Minded People#Stuff#Do Some Research#Make Tumblr ★ Great Again

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

Duel of the American Girl Dolls: Winners!

Elizabeth Cole's best outfit is : Riding Outfit

Cecile Ray's best outfit is: Meeting Outfit

Marie-Grace Gardner's best outfit is: Summer Dress

Caroline Abbott's best outfit is: Winter Coat

Nicki Hoffman's best outfit is: Red Vinyl Jumper

Isabel Hoffman's best outfit is: Year 2000 Outfit

Ruthie Smithens best outfit is: Play Outfit

Nellie O'Malley's best outfit is: Spring Party Dress

Claudie Wells best outfit is: Meeting Outfit

Courtney Moore’s best outfit is: Meeting Outfit

Emily Bennet's best outfit is: Meeting Outfit

Felicity Merriman's best outfit is: Riding Hat and Habit

Kaya's best outfit is: Pow Wow Dress

Josefina Montoya's best outfit is: Weaving Outfit

Kirsten Larson's best outfit is: Checked Dress and Shawl

Nanea Mitchell's best outfit is: Holoku Outfit

Maryellen Larkin's best outfit is: Poodle Skirt

Melody Ellison's best outfit is: Birthday Outfit

Rebecca Rubin's best outfit is: Meeting Outfit

Samantha Parkington's best oufit is: Plaid Cape and Gaiters

Molly McIntire's best outfit is: After School Party

Addy Walker's best outfit is: Tartan Plaid Dress

Kit Kittredge's best outfit is: Overalls

Julie Albright's best outfit is: Calico Dress

Ivy Ling's best outfit is: Chinese New Year Outfit

The best Truly Me Cute Dress is: Red Jumper

The best Truly Me Exploration outfit is: World Traveler in Ireland

The best collector doll is: Shimmering Silver

The best American Boy doll outfit is: Tartan Plaid Outfit

The best World by Us/Mordern Girl outfit is: Evette's Meeting Outfit

The best Truly Me Fun and Hobbies outfit is: Christmas Recital

The best Truly Me Beach Wear outfit is: Beach Outfit

The best Birthstone Collection outfit is: September Sparkling Sapphire

The best Truly Me costume is: Medival Princess

The best Girl of the Year outfit is: Kavi's Bollywood Outfit

The best Truly Me dance outfit is: Ruby Ballet

The best Truly Me winter wear is: Sugar Plum Coat

The best Truly Me casual outfit is: Plaid Skirt and Sweater

The best Truly Me bed time outfit is: Penguin and Robe

The best Truly Me sports outfit is: Ice Dancer Outfit

The best Truly Me holiday outfit is: Diwali Celebration Outfit

#duel of the american girl dolls#american girl#american girl doll#american girl dolls#polls#dolls#doll#doll collector#doll collection#doll community#dollcore#molly mcintire#ruthie smithens#ag dolls#historical dolls#doll clothes#fashion dolls#vintage dolls#historical fashion#caroline abbott#nicki hoffman#marie-grace gardner#cecile rey#elizabeth cole#isabel hoffman#claudie wells#felicity merriman#maryellen larkin#kaya#nanea mitchell

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE (2002) dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

#punch drunk love#punch drunk love 2002#pta#paul thomas anderson#omg this movie is so 2002#i love it sm#adam sandler#emily watson#mary lynn rajskub#phillip seymour hoffman#*mygifs#punchdrunkloveedit#filmgifs#filmedit#moviegifs#movieedit

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is cursed but Peter Strawm kills me

©markhoffm4n

#whoever had the idea to put a fcking straw there 💀💀#peter strahm#saw#saw franchise#tw mari#mark hoffman

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Impossible Task

The following short story written by Mary Hoffman is from the official Stravaganza-website, which doesn't exist anymore. It is accessible through the Wayback Machine, but I am uploading the short stories here to a) act as a secondary archive and b) to make them accessible to fans. If this story is ever re-published somewhere or I am asked to delete it, I will do so. This post will be unrebloggable, but feel free to link to it if you wish to add comments/discuss the story. I do not own the story, and it is directly copy-pasted from the old website (except for a link at the end which does not work).

---

Girolamo Miele, the greatest architect in all Talia, was in jail. Not for murder or theft or treason; he had forgotten to pay his Guild fees. And angry as he was with those who had plotted to imprison him, he was much more fearful of what his young wife Beata would have to say about his forgetfulness.

Miele paced the stone floor of his underground cell, only a few hundred yards from where he should have been working on the great unfinished cathedral of Giglia. He stopped to cast a critical eye at the vaulted ceiling of the cell; it was competently designed, no more. Still, prisons did not have to be more than functional.

But Girolamo Miele was a sculptor and goldsmith as well as an engineer and architect. And he believed that form and beauty were the same thing — if a thing functioned properly it would be beautiful in its own right and all ornament just a footnote, an indulgence of the maker. Mentally he began to redesign the dungeons, to pass the time till Beata would come with the money for his fine.

*

'Twelve scudi!' Beata had exclaimed earlier when the guards had come for Miele.

'You would imprison my husband, the great Miele, for non-payment of a sum that is less than he pays a labourer on the cupola for one lousy day's work!'

For that was what the missed dues to the Stonemasons' Guild amounted to: one scudo for each month of the year. But the fine was a hundred times the sum, a punishing one thousand two hundred scudi. It didn't matter to Miele; he had thirty or forty times that banked with the di Chimici family, who were the richest family in Giglia.

Beata and Girolamo wasted no time on enmity towards the guards; they knew who was really responsible for the arrest. The feud between Girolamo Miele and Ottavio Altamonte had being going strong for thirty years, since before Beata had been born, and this was just the latest skirmish.

The Rivals

In 1400, when the di Chimici were just coming into their fortune as bankers in Giglia, the Guild of Wool Merchants decided to hold a competition. The huge cathedral, Santa Maria del Giglio, Saint Mary of the Lily, was nearing completion. The crossing was still open to the sky, its floor messed by pigeons, awaiting a dome worthy of the mighty building conceived a hundred years before.

But in front of the cathedral façade, which was still rough brick at that time, stood a much more ancient building. The black and white striped baptistery was an octagonal structure, now dedicated respectably to Saint John, the patron saint of all baptisms. But there wasn't a single Giglian who didn't know that it had once been a temple dedicated to the Consort of the Goddess, the Sun.

Its very shape — eight sides representing rays of the sun — showed it to belong to the old religion of the Middle Sea, the one that Talians continued to believe in their bones, under the surface of form and doctrine that modern fifteenth-century men and women wore.

Talia had been converted to Christianity only a few hundred years before and only on the understanding that people could go on believing what they liked because no one was going to ask them. So Talians, and that meant Giglians as much as anyone else, built their churches and cathedrals but went on swearing 'By the Goddess!' They had their Pope in Remora, but never forgot that it had been capital of the Reman Empire when the Goddess and her Consort held sway all over the Middle Sea.

And in 1400 Giglians were afraid that they had perhaps not been paying enough attention to the old deities. There had been a terrible plague — the Cold Death they called it, 'Morte Fredda', because once the victims reached the shivering stage of the disease, they were doomed. A quarter of the city's inhabitants had died.

So the Guild of Wool Merchants had decided to cheer up the remaining three quarters by having a competition to do something magnificent for the old temple. Donato Nucci, who was leader of the Guild, wanted the people to let the Lady know that she and her fiery lover were still important to the city, that the vast bulk of the Christian cathedral rising over the old temple was no insult to the old gods.

So he authorised the Lana, the Wool Merchants, to pay for a pair of splendid bronze doors that would face Saint Mary of the Lily and remind all worshippers of the new religion that the old one was always nearby. The doors would show scenes from the Christian Holy Book but ones that could be interpreted as representing older stories. The prize would be 80 silver florins and was open to all sculptors in Talia. The cost of the materials would be borne by the Guild and the competition would be judged by a special committee.

The scene to be depicted for the competition was that of the Maddalena weeping over the dragon. It was an enormously popular story with Talians because it had two meanings. The one in the Holy Book was that the reformed sinner wept over the creature because it belonged to the pagan past, which would dissolve under the influence of the new faith. That was what the Archbishop of Giglia could believe when he came to bless the doors.

But in the older version the Saint was none other than the Lady herself and the dragon was the new religion, which would devour her. She wept then because she saw how the future would be but the ravening beast dissolved at the first drop because, after all, the Lady cannot be driven away; she will always find new forms.

There were at least seven serious contenders but only two matter for this story. Ottavio Altamonte was a young lad of twenty, untried and inexperienced but good-looking and extremely polite. Girolamo Miele was twenty-four and had cast bronze before but was ill-favoured and not possessed of the sweetest temper. While the competition panels were being made, Ottavio sought advice from every artist and person of judgment in the city. No one was allowed to look at Miele's work, except his great friend the sculptor Gabriele.

Now this Gabriele was no better-looking or more polished than his friend, but the two men had known each other all their lives, had both been born within sight of the rising cathedral and were passionately loyal Giglians. Gabriele had sculpted in marble, cast in bronze, carved in wood and could represent anything he saw and lots of things he didn't.

Miele was more interested in how things worked; if there was no tool or device available to make the piece he was working on, he designed and made what he needed. Recently he had become interested in buildings and taken to hanging round the stonemasons working on the cathedral. He knew of the problem that no one was sure how the vast apse could be domed and had taken to making sketches in chalk and charcoal on the walls of his father's bottega, where he was still apprenticed to him as goldsmith.

The dragon panel had to be worked on after hours, when everyone else had gone home. Miele would hurry back to his parents' house and gulp down a quick supper then return to the workshop, entrusted with the keys, and work on, sometimes till dawn.

'That boy's digestion will never recover from this competition,' his mother said, shaking her head.

And she was right, for Miele's dyspeptic disposition was made much worse at this time, both from snatched meals and from hearing his rival's work praised wherever he went. It was Young Ottavio this and Dear Altamonte that all over the city. Rumours were circulating that the younger man was sure to win: his Maddalena was a miracle of beauty, bending over the dragon so realistically that you could swear you saw the tear fall.

Miele spent his time drawing the little lizards that dozed on the hot paving stones in the yard, until he had perfected his knowledge of how their scales fitted into the pattern of their elegant skins. 'Dragons in miniature,' he called them. But when Girolamo had finished the first model for his panel, Gabriele saw that the dragon was to be immense.

It dominated the scene, towering over the Saint, who was not beautiful; she was a small, weary woman, whose tears must have dropped on no higher part of the beast than the clawed foot he was extending to her.

'It will be your masterpiece,' said Gabriele. 'You are bound to get the commission. And be known as the greatest sculptor of the fifteenth century.' He felt no jealousy as he said it; fine artist though he was himself, he was awed by his friend's great talent.

But the committee decided differently. The great efforts made by Ottavio to get its influential members on his side had paid off. And his panel was undeniably very fine, in a style the judges were familiar with. They saw Miele's as ugly and possibly subversive: hadn't he shown the dragon much larger than the Saint? No, Altamonte was the safer choice and so the florins went to him.

Exile and Return

Miele was so disgusted that he would not stay in Giglia another day. He packed a bundle of tools, told his father his apprenticeship was over, and set out for Remora. On the road, he was overtaken by his old friend Gabriele.

'I am bound for Remora too,' he said. 'I find the air of Giglia does not agree with me at present.'

Nineteen years the two men stayed in Remora, studying the old Reman ruins, digging up broken statues and measuring the remains of fine buildings. They had lodgings in the contrada of the Lady and news reached them often from their home city, where Ottavio was working on his doors and growing rich on other commissions.

In all this time, Miele did not cast another bronze or make another statue. But he built two churches and was designing a third when momentous news came from Giglia. There was to be another competition and this time it was to build the dome for the cathedral.

'It's an impossible task,' objected Gabriele.

'Exactly!' said Miele, his eyes gleaming. 'That is why is must be me that takes it on.'

So the two friends re-entered the city they had left nearly twenty years before. Miele's father had died and the workshop had been sold but the two men had enough money from their Reman ventures to buy another, even closer to the east end of the cathedral, where the cupola would rise above them.

Gabriele's reputation as a sculptor had grown in his absence and commissions were soon coming into the bottega for him. Miele did nothing but sketch and make models for the dome, spending more time in the unfinished cathedral than in the workshop. He had heard that Ottavio was making a model too and he was determined not to be beaten again. And this time the prize was 200 silver florins.

While the Giglians had been away Ottavio had finished the bronze doors and was now one of the richest artists in the city. He wore silver-trimmed velvet and jewelled rings, while Miele and Gabriele preferred homespun and kept their hands unadorned so that they could work the better.

When Miele's full-scale model of the dome was built, out of real bricks, Gabriele lent it all his skills of ornamentation, even down to a miniature Giglian flag flapping from the top of the cupola's lantern. The dome was divided into sections separated by ribs to be clad in white marble. But the secret ingredient was hidden inside it: the method by which it was to support itself without scaffolding as it rose from the existing building. Miele wouldn't tell anyone that — not even Gabriele.

How to support the dome was exercising Ottavio's ingenuity too. He knew that was the important issue. Most people in Giglia did not believe the dome could be built without internal scaffolding. But to get enough wood to build the centring would be almost impossible. So in the end, he decided to be as mysterious as his rival.

The big day of decision came and the field was as before narrowed down to two: Girolamo Miele and Ottavio Altamonte. Miele was more confident than last time; he knew he could build the dome. But unfortunately his confidence came across as arrogance. Ottavio, on the other hand, was all smiles and charm.

The new dome committee became more and more alarmed as Miele explained his model. He waved his arms about wildly and the words came tumbling out in the wrong order, falling over each other and tripping up his tongue. The committee didn't even let him finish before asking Ottavio to explain his plans. And at the end, they asked the younger man to build the dome.

Building

This time, Miele didn't run away. He got married instead. Gabriele was surprised how calm his friend was after his disappointment about the competition. He was normally so fiery and proud about his work. Instead, he accepted a commission to build the Ospedale della Misericordia and proposed marriage to Beata, the daughter of his housekeeper.

It was a fine match for the girl but the artist was more than twice her age and not much to look at. She began by being a little afraid of him but soon learned that he had a good heart and in time realised what a great mind he had too. Fear turned to respect and then to love, particularly when she saw him with their first child.

Gabriele was quite astonished; he had assumed the two friends would have grown old together as confirmed bachelors.

'You should try it yourself,' said Miele, dandling his baby son on his knee. 'A warm wife in your bed, a good meal on the table, a boy to pass your talent and your wealth on to and work of the kind you love — what more could a man ask for?'

But there were other sources for his contentment. All the time that he was working on the building that would be the Ospedale, Miele was getting news from the cathedral that work on the dome was proceeding at a snail's pace. The committee was unhappy but Miele just smiled. The model of his own design still sat in the courtyard of his bottega, its pointed cupola complementing the huge nave and side chapels.

And all the while the bricks crept slowly up the real thing, as Ottavio wrestled with the problem of building such a huge cupola without scaffolding. Giglians began to say that it would take the intervention of the Goddess to get the crossing vaulted. Five years after the competition Miele had a wife, two babies and a third on the way, and the Ospedale was finished, to the wonder of all the masons of Giglia. It was the most elegant and beautiful building the city had ever seen, with its stepped loggia and slender columns supporting curved arches.

Ottavio was having to justify to the committee four years of paying a huge team of workmen with very little to show for it. He put on a spurt, urging the men to lay more courses of bricks in a few months than they had in the past two years. The dome was beginning its inward curve.

And then came disaster. The plague returned to Giglia. The people were superstitious and when the first citizens began to shiver on the same night that four courses of bricks fell into the cathedral from the growing cupola, they felt sure the catastrophes were linked. Fortunately, since it happened at night, there was no one in the building to be hurt. But Ottavio was deeply damaged in his reputation: now when people passed him in the street they made the Hand of Fortune and crossed to the other side.

Rescue Mission

The knock on the door was not altogether unexpected. Miele and his family now lived in a substantial house not far from the bottega and they kept a servant-girl, who opened the door to the senior members of the cathedral committee. It was evening, three days after the cathedral dome had caved in, and they were shown into Beata's little parlour.

Big with child, Beata levered herself out of her chair to find refreshment for them, providing also all the niceties of welcome and conversation, because Miele remained resolutely silent. He was going to let them sweat.

But by the time they left, Miele was made capomaestro of the cathedral, on a salary of 200 silver florins a year. His one condition was that Ottavio should have nothing further to do with the project.

The first thing that Miele did was to get the masons to undo all the bricks they had laid, so that he could start with a clean slate. By three years later, the dome was rising strong and curved against the blue Giglian sky, supported and sustained by all manner of architectural devices: rings of wood, stone and metal were embedded in the brickwork, two shells rose at the same time, an inner and an outer dome.

Miele was by now the father of three sons and two daughters, although Gabriele was a bachelor still. Alfonso di Chimici had succeeded his father Ferdinando as head of the family and the bank. Ottavio Altamonte was making another set of baptistery doors. His reputation as an architect never recovered from the collapse of his dome, but he still got many lucrative commissions as a sculptor. He was wealthier than Miele, for he had no family to feed, but his resentment of his older rival festered on.

And so it was that the great architect Miele languished in a dungeon while his wife fetched the money for the fine from Alfonso di Chimici and Ottavio ate a good dinner in his house on the other side of the cathedral. When Beata came to secure his release, Miele was sleeping peacefully on a straw mattress.

As they walked across the piazza dominated by the great cathedral, Ottavio just happened to be taking an after-dinner stroll. The two men came face to face for the first time for many years. Ottavio doffed his plumed hat with elaborate courtesy. Beata was inclined to be frosty but her husband was feeling mellow. His younger rival had not a thing that he wanted; Ottavio's wife was barren, the dome had been taken away from him and, against his feathers and velvet, the man's skin looked sallow and his eyes lustreless.

'I trust I find you well, Maestro?' said Ottavio politely, his dull eyes taking in the straw that still clung to Miele's hair.

'Never better,' replied the architect. 'I have had a delightful and unexpected rest. And I have used it to design the crane that I shall need to hoist the marble up inside the dome for the lantern that will crown it.'

'You are confident then of finishing the dome?' said Ottavio, his lip lifting in a perceptible sneer. 'You must have been praying to the Goddess.'

'No,' said Miele, putting his arm round his wife's comfortable waist. 'I think others have been doing that. I think that their prayers were answered three years ago when I was appointed capomaestro.'

Then he felt sorry for the man and put out his hand to shake the other's more sincerely.

'Messer Ottavio,' he said. 'Is it not time to put aside all enmity and work in harmony for the beautification of our city? We do not expect a musician to write poetry or a mason to weave silk. You are a fine sculptor and your doors are a miracle. Leave the dome to me and the Goddess.'

Something thawed a little in Ottavio's chilly heart. He only nodded.

But many years later, when the dome was finished and the cathedral had been consecrated and the great master-architect Miele had been laid to rest under its nave, two bronze statues stood in wall niches above it. One was by his dearest friend Gabriele. But even though Gabriele was now acknowledged as the finest sculptor in bronze in all Talia, there were those who said that the likeness cast of Miele by his life's rival, Ottavio Altamonte, was even finer.

Note: I have taken great liberties with art history of the Renaissance here. Filippo Brunelleschi was never married and Lorenzo Ghiberti tried his hand on the dome only briefly. For the real story behind the Cupola of the Duomo in Florence, you can read Ross King's Brunelleschi's Dome (Chatto & Windus, 2000) and Paul Robert Walker's The Feud that Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World (William Morrow, 2002).

There are great websites at:

But in Talia, the Giglian architect, Girolamo Miele, was the ancestor of sculptor Giuditta Miele, who is a character in City of Flowers.

3 notes

·

View notes